Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

November 4, 2019

by Joyce Gannon

After a Sunday morning shooting in 2013 left two people dead at an after-hours club in Homewood, the building was shuttered and its windows boarded up.

Two years later, Bible Center Church — a congregation with a mission to bring change to the neighborhood through social innovation — bought the vacant structure and one that adjoins it on North Homewood Avenue in the heart of the community’s commercial district.

As renovations continue, the buildings are filling with activities that John Wallace, Bible Center’s pastor, hopes will spark small-business ownership in the tattered neighborhood that once boasted blocks of thriving retail and mom-and-pop enterprises.

“The idea is to redeem the space,” said Mr. Wallace, also a professor who teaches social entrepreneurship at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Social Work.

That site is one of several in Homewood where Mr. Wallace’s church and other organizations are trying to foster entrepreneurship in an area long plagued by crime and poverty. His vision is for the presence of black-owned businesses and jean-clad black entrepreneurs to become the norm in a spate of buildings that offer space for them to talk shop and go over business plans.

A hub of startup programs

Last month, Bridgeway Capital opened the Sarah B. Campbell Enterprise Center at 7800 Susquehanna St. The former factory built by famed Pittsburgh entrepreneur George Westinghouse’s company also houses small manufacturing firms, makers and artists.

A black barber and an artist anchor The Shop, which opened in 2017 in a former auto-body garage on North Dallas Avenue as a coworking and community events space. That site recently hosted a Saturday workshop series for entrepreneurs and serves as a meeting space for Black Tech Nation, a networking group for professionals, entrepreneurs and students.

Among future tenants slated for the Bible Center Church property on North Homewood Avenue is Own Our Own, an entrepreneurship academy Mr. Wallace founded this year for individuals who have ideas for enterprises but lack financial resources, mentors and role models.

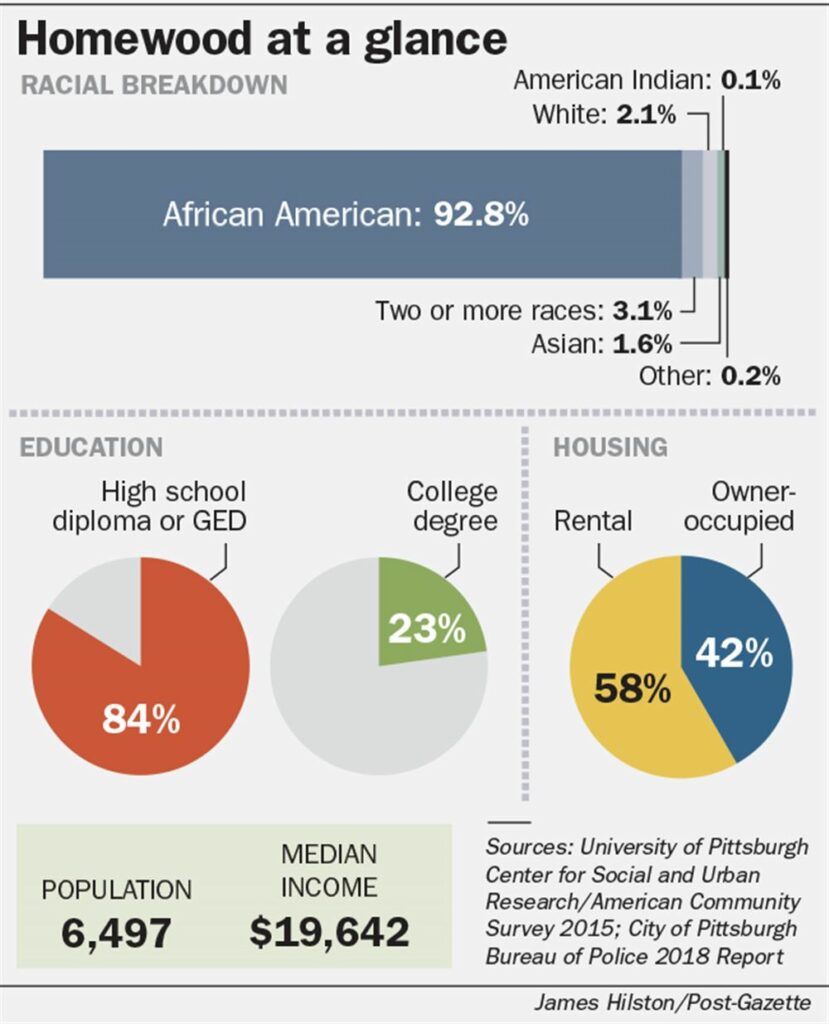

The Own Our Own program targets black men and women — a group that comprises more than 90% of Homewood’s population and historically has low rates of business ownership in Pittsburgh.

“That was the piece missing,” Mr. Wallace said. “I see us at the front end of a pipeline for a population that, frankly, has not been included.”

In addition, in the building that adjoins the space Own Our Own will occupy, Pitt last year opened a Homewood Community Engagement Center. It offers business assistance through the university’s Institute for Entrepreneurial Excellence.

The program, which focuses on growing “Main Street” firms in distressed and underserved neighborhoods, includes a six-month certificate program for business owners.

“We’re bringing the education element to people who may not have gone through formal education to set up a business,” said Nicole Hudson, senior program manager for Pitt’s Urban & Community Entrepreneurship Program.

Since Pitt’s engagement center opened in October 2018 and began offering free one-on-one counseling, Linwood Mitchell, senior financial management consultant, has met with local contractors, personal trainers, food vendors, child-care providers and others.

Other ventures Bible Center Church has launched in the last several years include Everyday Cafe, a cashless coffeehouse; and Oasis Farm & Fishery, a bio-shelter where Homewood residents learn to grow and sell healthy food.

“I believe that the proliferation of small [business], even microbusiness, ownership can have a tremendously powerful impact, not only economically, but also psychologically, on communities like Homewood,” Mr. Wallace said.

From shot-up windows to food startups

Over the last 15 years, Bible Center Church has invested about $600,000 in Homewood real estate.

Among the properties it bought was a long-vacant building at North Homewood Avenue and Bennett Street that formerly housed a Rite Aid and “literally had bullet holes in the windows when we bought it,” said Mr. Wallace.

That building is now a worship space and is used for youth entrepreneurship programs and other activities. One level is being converted into a commercial kitchen which could help Everyday Cafe expand its catering operations and provide working space for food startups.

Mr. Wallace, 54, knows firsthand the challenges of igniting change in one of the poorest pockets of the city.

He grew up on North Homewood Avenue, and his grandparents in 1956 founded the church he now leads. He left for college in the 1980s, when the city’s manufacturing base was in free fall.

By the time he returned in 2004 — after graduate school and a stint teaching at the University of Michigan — many local shops had disappeared, the commercial district had deteriorated and people were moving away.

According to a report from Pitt’s Center for Social and Urban Research in 2015, about 40% of Homewood’s residents lived below the federal poverty level, which at the time was $24,250 for a family of four.

Its reputation for violent crime was spotlighted in July when an off-duty city police officer, Calvin Hall, was shot after attending a party on Monticello Street. He died three days later.

The perception of crime is a barrier to businesses like Everyday Cafe, which would like to attract more customers from outside Homewood, said Catherine Lada, formerly an adjunct faculty member at Pitt’s College of Business Administration and the Joseph M. Katz Graduate School of Business.

Ms. Lada, now director of marketing and communications at the Global Cold Chain Alliance in Arlington, Va., was a consultant with Bible Center Church who helped launch Own Our Own.

Crime is less of a factor for most entrepreneurs in that program, she said, because they have “microbusinesses … where the direct neighborhood is generally the customer pool.”

Pursuing passions

Seven individuals enrolled in this fall’s 12-week Own Our Own cohort include a jewelry maker, a chef, a web designer and an event planner.

“They are lifestyle businesses that are not going to necessarily explode and hire a bunch of people,” said Mr. Wallace. “But a one- or two-person business can boost the entire economy.”

Some ventures will likely be second jobs for people who want to pursue their passions and generate extra income, he said. “For people baking at their dining room table, an extra $10,000 to $12,000 a year could be a game-changer for their family.”

The cost to enroll in Own Our Own is $249.

At the Sarah B. Campbell Business Resource Center, 2,100 square feet of open space with movable tables and chairs is flooded by natural light from the former factory’s large windows.

Makers who rent studios on the floors above and members of Bridgeway Capital’s Craft Business Accelerator created bright colored light fixtures, tiles and other accessories in the space named for a longtime black social activist in Homewood who died in 2018.

Bridgeway Capital staffs the resource center — which is open by appointment and is accessible to building tenants and others in the community — with lending and marketing specialists.

Since Bridgeway bought the five-story 7800 Susquehanna in 2013, much of the interior’s 150,000 square feet has been rehabbed. It’s 100% occupied, said Katherine Chamberlain, Bridgeway’s director of communications.

The building’s 24 tenants include the Trade Institute of Pittsburgh, which trains people coming out of incarceration, and Pitt’s Manufacturing Assistance Center, which offers programs such as machinist training and computer-aided design technologies for veterans and others.

Heather and Myles Geyman, whose Stak Ceramics studio leases 2,000 square feet, like that the space is accessible to other small maker firms they tap for input on business challenges. The couple, who moved in four years ago from storefront space in Sharpsburg, design custom pieces like planters for FTD and desk accessories for office furniture giant Steelcase.

“There’s good energy and working collaboration in the building,” said Mr. Geyman, whose business has two full-time employees besides the founders.

Matching Pittsburgh’s gains

In the end, Mr. Wallace aims to jump-start enough activity in Homewood to rival the economic growth much of the Pittsburgh region has enjoyed in recent years.

“My dream is for opportunities and outcomes in our ZIP code to match the opportunities and outcomes in Pittsburgh’s area code,” he said. “If 15208 can equal 412, I would feel successful.”

He figures he has an advantage.

“I’m a Homewood kid; I can make the connections.”

Read the Post-Gazette article at: https://www.post-gazette.com/business/bop/2019/11/04/Homewood-entrepreneurship-business-pittsburgh-Bible-Center-Church/stories/201910210110